Chapter Six

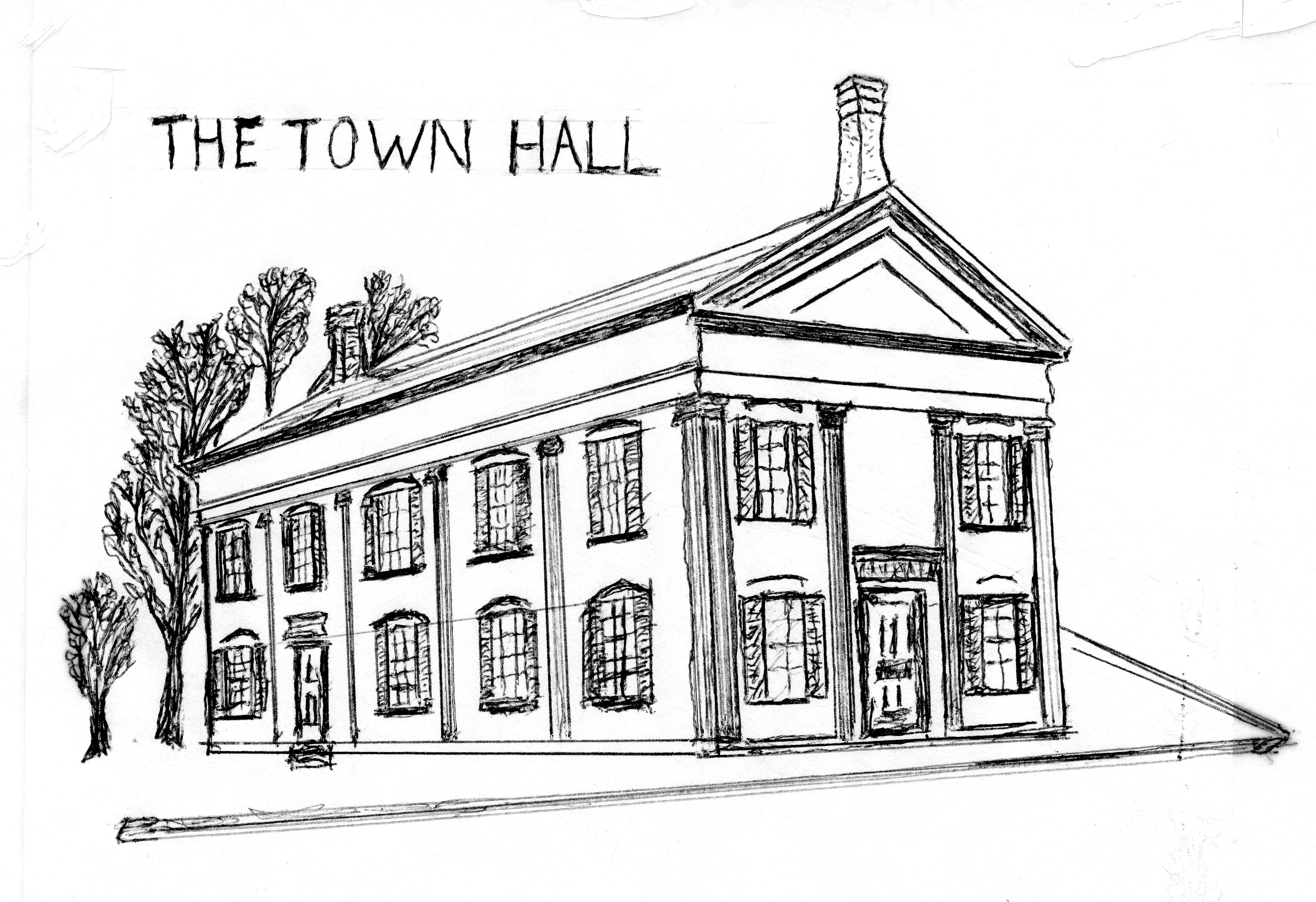

THE TOWN HALL

Town Meeting, Library, Social Center, Basketball

Among memories of my early school years, the Town Hall is dominant. It was situated on the East-West thoroughfare from New Haven Junction to Bristol, near the centrally located elm-treed area known as "The Park" and between Charlie Everest's store and the farm buildings across the highway. It was built sometime in the mid-nineteenth century but it burned to the ground a year after I graduated from high school in 1936. Some of the most cogent memories of my early youth derive from activities and associations there.

It was a rectangular two-story building and the town civic center, but much more: theater, recreation hall, dance hall, card parlor, basketball court or any other event that required a meeting place.

The first floor, as I remember, had a cloakroom inside the entrance, an auditorium with folding tables and chairs, and in the rear a small kitchen, an administrative office (though I seem to recall the town clerk worked mainly out of his home at his personal desk) and in the rearmost corner, the community library.

The library was small by any standard with windows at the rear and side, a desk for the librarian and bookshelves along the ends and sides and two shelves bisecting the room's length.

During the Depression years of the late 1920's and well before the airwaves provided commercial entertainment, reading was our principal diversion. Soon after we started the second grade our teacher would lead us down to the Town Hall and into the library where we would be individually issued our library identity cards. It was a significant and aggrandizing moment -- from that day forward we were entrusted with precious personal access to the world of imagination.

I know that I must have read all the books for small children, but remember few titles beyond the Peter Rabbit variety. I do recall the many brave and heroic boy stories such as "Tom Swift and His Flying Machine" and the Hardy Boy series and others about heroes and pirates and boys and dogs and boys aplenty.

In the neighborhood or schoolyard we would occasionally obtain copies of popular paperbacks featuring World War I American and German flying aces in their respective SPADS and FOKKERS and illustrations depicting defeated enemies making flaming descents.

In junior high and high school, the library (pronounced "liberry" by most of us) was a continuing source of assigned reading and recreational literature. By the time of high school graduation, my inveterate reading habit had just about exhausted the inventory on those precious shelves.

My memory of activities in the main hall of the first floor are less distinct, but I do recall card parties of whist (the terms "right and left bower" pop into mind but their significance is long gone) and youngsters playing "King Pede" (we chose to consider it a verb rather than a noun, but the name was not descriptive of the game either way). I knew there were many other ladies' affairs involving luncheons and the like but my activities there were few as are my memories.

The second floor was another matter. During my pre-teen years when a few horses and buggies still might be hitched outside, it was the community gathering place for the intellectual, the theatrical, the political, the musical and the social. I recall my parents going to hear circuit lecturers and touring players. Local groups staged their own popular, usually melodramatic, plays. My father participated in annual minstrel shows, blackface parodies with the "Interlocutor" in the center directing the action and the "end Men" responding with corny jokes and witticisms frequently referenced to the more prominent citizens in the audience.

I must interject that at that place and time we had not the faintest conception or sensitivity to black culture beyond our reading of "Uncle Tom's Cabin" or "Huckleberry Finn." There were no black persons in our community and the only one I ever saw personally had a shoe-shine stand in Bristol. It was a time when radio featured "Amos and Andy" and the actors were white, faking black accents. It would take World War II to widen our horizons.

Also at the Town Hall musical groups were programmed; dances, both round and square, were sponsored by local associations with appropriate refreshments provided from the kitchens below or brought from home.

Downstairs in the corners, or outside in the shadows, a few men would gather for surreptitious nips of Canadian whiskey or whatever may have been distilled in the sugar house or some other location near home.

In truth, the Town Hall was the solution for any kind of community social activity too large for the family home or inappropriate for church or school. It provided its most valuable and timely service to the men, women and children of New Haven in those years before wide ownership of automobiles and improved roads permitted easier access to facilities for shopping, entertainment and medical assistance in the larger outlying towns of Bristol, Middlebury, Vergennes and, on occasion, even Burlington.

The top floor of the Town Hall also served as the home court of the boys' and girls' basketball teams. Our games were often played at night after chores and usually in wintery weather.

For any stranger trying to envision a game of basketball as played on the top floor of the Town Hall, a preliminary description of the physical layout is important.

The Hall was not large so measures were taken to utilize all feasible square footage. The floor was cleared and the folding seats moved downstairs and a few placed on the stage for spectators. At the far end of the court in front of the raised stage, a basket was suspended with its supporting structure placed in a narrow recess built for footlights during stage plays. It would occur frequently that during the fervor of competition a player would launch himself into the footlight area or onto the stage itself.

At the near end of the court, close to the hall entrance, boundary lines had been drawn to provide the maximum possible length to the playing area. There was room only for a huge pot-bellied stove, glowing red in winter and shielded by an asbestos cover, but near enough to the court for frequent contact with flying adolescent bodies. Also, room was made for standing and sitting coaches, substitutes, and a few influential bystanders. Above them a backboard and basket projected outward from a structure framed against the near wall.

With the problem of end boundaries solved, the framers determined that adequate court width necessitated defining the side limits by lines drawn six inches from the building walls (meaning that spectators on the stage could not leave their seating area for any reason except during official cessation of play).

Three large windows, starting at floor level, bordered either side of the playing area necessitating the structure of heavy screens lest accelerating young bodies crash against them with risk of broken glass and serious injury.

The building had one other structural singularity that necessitated special play and house rules. The ceiling curved so that the outer edges were lower than the middle. Additionally, from where the curved ceiling began at the sides, two reinforcing crossbars stretched across the court about a third of the way from either end. Consequently, in taking a shot from midcourt, one would loft the ball over the bar, and correspondingly, a little farther forward, one would attempt to launch it under the bar. Understandably, the physical layout was advantageous to the home team.

Local rules were established as follows:

1. Balls striking the walls or window screens were out-of-bounds and surrendered to the opposition. Players striking walls were not penalized and if pushed earned two free throws.

2. Balls striking the overhead rods were played as if out-of-bounds even though they fell back to the playing surface.

3. Due to the close proximity and usually raucous behavior of the crowd, the official could award one foul shot to the opposition at his discretion up to a limit of one per quarter.

It could not have been the same game I observed our grandsons play. Our winning score would rarely exceed twenty points.

A telling fact could be that I, a varsity player during my final two years in school, measured five feet four inches tall and weighed one hundred twenty pounds, reflecting the size of our enrollment at Beeman Academy, a quality educational institution about which I will have more to say in the next chapter.